Cancer News Updates Everyday – Unending Information & Discoveries

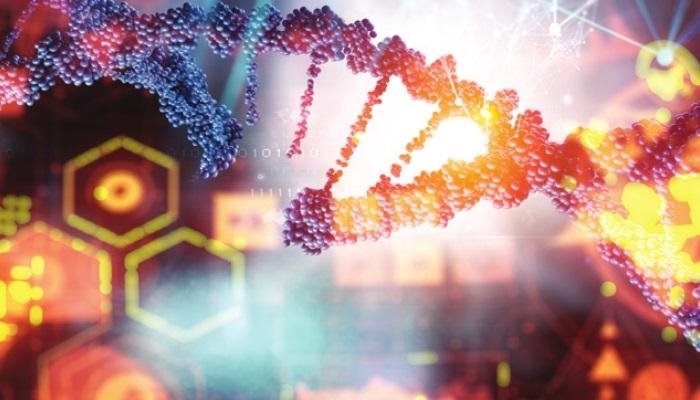

There’s simply no way any person can be abreast of all the knowledge. We need to interact with people; we cannot sit alone in a clinic and treat anymore. We need to consult with the pathologist, molecular oncologist, pharmacist, and others. We have to get patients into clinical trials, get patients into drugs that will help them live longer, and have that conversation with the patient. It’s important to focus on the cost as well as the benefit, and if we are genuine with patients, a lot of them are benefiting in both ways. You do not want them to undergo unnecessary treatment and spoil their quality of life, but at the same time, you want to give them the best and overall longest life possible. Dr. Saadvik also agrees that learning is a never-ending process, and in oncology, it’s a daily process. He also agrees that research has picked up in the last five years, but now the pace is such that every month something new comes up, and that is changing the standard. Today, you tell your patient that this is their plan for the next year or two, and six months later, you may have to counsel them again, explaining that the plan has been changed due to a change in the standard. It may look complex as of now because a lot of data is being pumped in and a lot of things are coming up, but in five to ten years it should get more simplified because of better understanding with more research and better drugs available.

Dr. Shrikar thinks the phrase to use is “cautious optimism.” He absolutely agrees with Dr. Sudha that the low-hanging fruits have already been obtained, we are not going to get another Imatinib for CML or another Dasatinib for EGFR mutant lung cancer anytime soon, and driver mutations that you target and get excellent responses have already been obtained. At the same time, when we hear of things like tumour agnostic approvals and blanket approvals based on small studies and single-arm studies based only on response rates—that is, the drug only shrinks the tumour but actually does not make an impact on the patient’s lifespan—we should pause, reflect, and see the reason for approval and whether it’s actually relevant to our day-to-day practise and whether the patients actually benefit from such blanket approvals or not.

For example, a blanket approval was given for high tumor mutation burden across all cancers, but that was based on a single-arm study with a response rate of 30, which means that 70 patients do not even respond to the drug despite it being given. Recently, a phase III trial that tried to show an improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in a randomised way based on tumor mutation burden failed to show an improvement in PFS, so that is where these thin lines come in. These were the thoughts of the young physician who has started his journey into the world of oncology.

Dr. Shrikar also feels that the pace of these drug developments and approvals is not keeping up with the developments in translational medicine and genomic sequencing, so there are a lot of imbalances between these two, and it’s up to physicians to act as stewards and shift through this huge volume of data that is coming our way and apply it for the best interests of patients. Dr. Kalyan believes it was very well articulated and asks if the audience has any questions for the panel.